by James Collector & Nicole Wires

As a permaculture landscaping company, Planting Justice’s Transform Your Yard (TYY) Team prides ourselves on the ecological thinking behind our installation projects. Typical projects include edible gardens, California native and habitat gardens, food forests, greywater systems, and rainwater catchment systems.

Photo: A Planting Justice permaculture garden in Oakland (occupied territory of the Ohlone people)

Although we prioritize using on-site resources, meeting the visions of our clients often requires that we source large quantities of raw materials. From mulch and soil to stone and lumber, the materials that we purchase from suppliers around the Bay Area can have mysterious origins. We often find ourselves asking, like many consumers in America, “Where did this thing I’m buying come from?”

The answers can raise hundreds more questions. Even ostensibly benign materials such as gravel and sand may have origins in distant pit mines owned by international companies whose business practices negatively impact low-income communities and fragile ecosystems. The pictures of the pit mines are shocking, some visible from space.

Photo: Kennecott Copper Mine, outside of Salt Lake City, Utah (occupied territory of the Ute, Shoshone, Paiute, & Goshute peoples)

With over fifty percent of the world’s population now living in cities, it is dangerously easy to remain oblivious to the rural origins of the materials that make up our cities.

Our resolve to improve our sourcing was recently catalyzed by Lucy R. Lippard’s 2014 book, Undermining, described as “a wild ride through land use, politics, and art in the changing west.” Lippard pushes her readers to consider the unseen sources of some of the basic building blocks of our cities. “Gravel is today’s plebian gem of choice — consistently valuable in the larger scheme. The aggregate industry (gravel, crushed rock, and sand) is “easily the largest mining industry in the country,” fueling 10,000 quarries and employing 120,000 workers. (Lippard, p. 27; data source).

Photo: Geneva Rock’s operations at Point of the Mountain, straddling Utah and Salt Lake Counties (occupied territory of the Ute, Shoshone, Paiute, & Goshute peoples) Source: Trent Nelson | Tribune file photo

It’s hard to admit that, while building food sovereignty and native-species habitat for communities in the Bay Area, we may also be unwittingly supporting irresponsible land-use elsewhere in the American West. Nothing stings the pride like realizing your own hypocrisy. So, with humility, we’ve begun to ask ourselves difficult questions: What kind of permaculture projects can we build without using virgin materials? What sacrifices do we need to make in order to build in alignment with our values? How can we meet our clients’ visions without compromising our own?

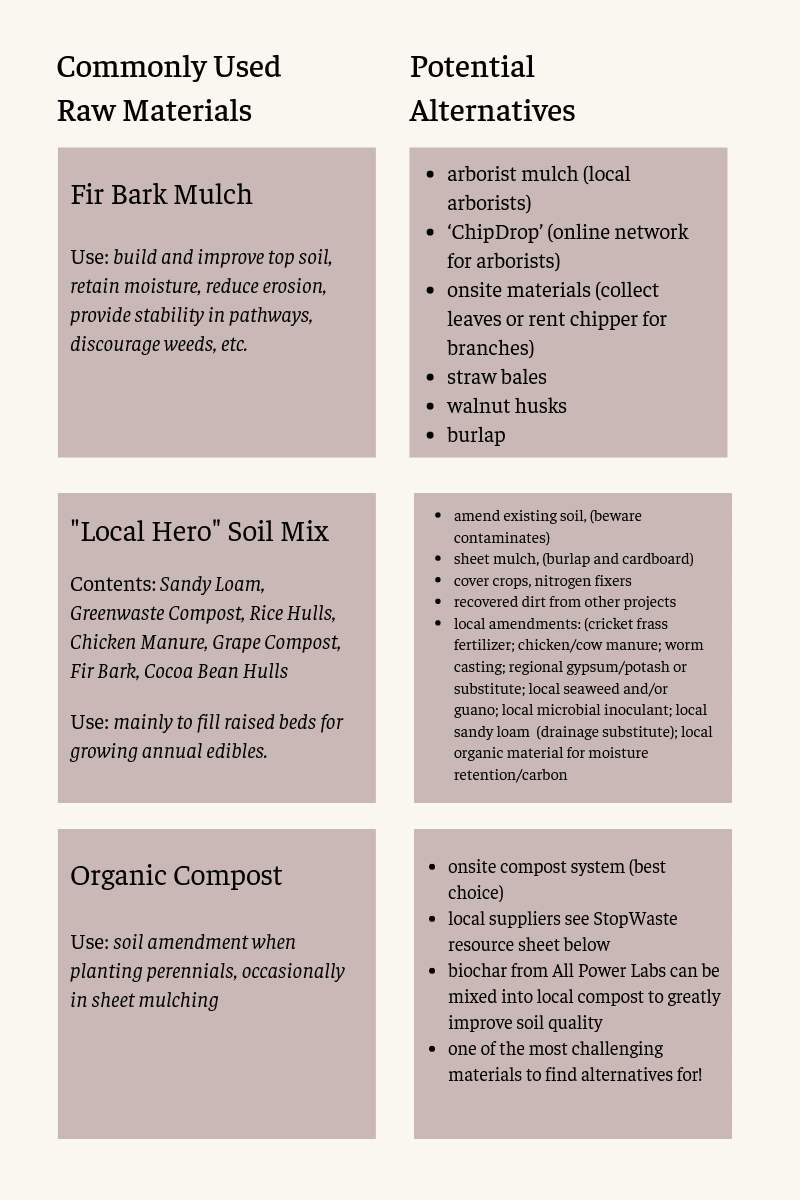

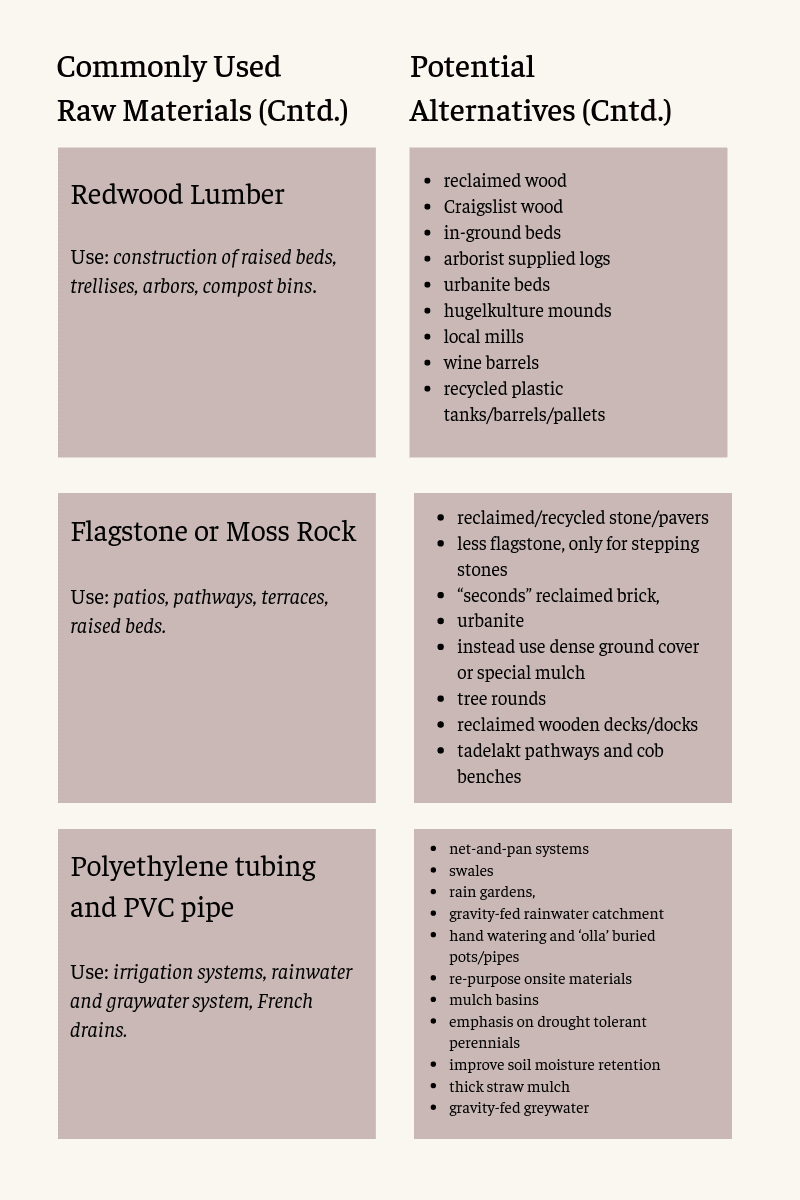

To answer these larger questions, we’ve re-examined six of our most commonly sourced materials. Here is a table pairing them with potential alternatives:

Ecological Alternative Materials infographic by James Collector & Nicole Wires

Note: the alternatives in this table are intended as starting points rather than prescriptive methods or specific sources.

Research into these alternatives requires time and resources. Some organizations might consider this information proprietary in order to maintain an advantage in the market (a short-sighted tactic as there will be no market without a healthy ecosystem). Instead, we’ve decided to share this information in hopes that other landscaping companies here in the Bay Area (and beyond) can choose to reduce their impact on distant communities and ecosystems.

Landscaping Dialogues

Speaking directly to other landscaping professionals: We understand that much of this comes down to client choice. Steering clients towards low-impact installations can be difficult, especially when a client has sentimental attachments to, say, a flagstone patio like the one they had growing up. So, it’s up to us as permaculture professionals to explain why to refrain from using virgin materials. Instead, we can work with clients to ask questions like, “Are there reclaimed stones or bricks or pavers that we can use to build a patio? Could mulch or groundcover substitute for hardscape? Is the beauty of flagstone worth knowing it was extracted from some distant site and shipped at great economic and environmental cost?” Sometimes, the client may decide it is worth that cost, but by opening up the conversation, other elements in the landscape may be built with reclaimed materials.

Inspired by Lippard’s book, we wrote this post to be a resource and impetus for more of these important conversations between landscapers and clients. The book’s title, Undermining, has become a mantra, a reminder of all the meanings underlying a conversation that appears on the surface to be simply about mulch or flagstone. Lippard explains: “The title, Undermining, has been attached to the project since its haziest inception: undermining literally — as in pits and shafts that reflect culture, alter irreplaceable ecosystems, and generate new structures; undermining’s physical consequences, its scars on the human body politic; undermining as what we are doing to our continent and to the planet when greed and inequality triumph; undermining as a political act — subversion is one way artists can resist.” Lippard’s book can be ordered here.

Photo: Open pit mines outside of Green Valley, Arizona (occupied territory of Hohokam people) as seen from satellite

In a culture that tends to commodify every possible resource, we are defined as much by what we choose to avoid as by what we support. Pictures of the vast pits from which the gravel for our concrete cities and the copper for our electronics have changed our approach to landscaping. When permaculture installation becomes a business, there is an incentive to build and sell more to increase revenue. The trade-offs between time and cost can create ethical dilemmas — fast and cheap solutions often entail unseen environmental consequences. Inversely, many labor-intensive permaculture techniques provide much-needed jobs yet require higher budgets. The trick is to find the balance, work with intention, and know when to say, ‘no, thanks.’ Or as our co-worker Patrick Dunnigan says, “Slow down and move at the pace of nature.”

Photos: A bountiful community garden installed by Planting Justice’s Community Justice Garden Program in San Francisco (occupied Ohlone territory) at Farming Hope pictured in three consecutive months. Photos courtesy of Farming Hope & brontë velez

Three Examples

Three of the most common materials we work with are compost, mulch, and soil — all fundamental to a permaculture landscape, yet each bringing nuanced challenges in ethical sourcing.

Compost presents the central challenge of imported amendments vs. ‘on-site materials.’ In short, nothing beats an on-site compost system. Beneficial bacteria and fungus are geographically specific, adapted to local micro-climates. Given this, imported compost never works as well as on-site compost. Compost can be generated in nearly every location. The key is to work with what is locally abundant. It takes some work but the degree of management is flexible. Some folks want to turn over their compost every 3–6 months. We think the realistic expectation for an average homeowner is once a year. The volume will add up in the long run. One 3-foot by 3-foot compost bin turned over and spread across the landscape could add an entire cubic yard of on-site compost every year — equivalent to about $50 worth of store-bought compost. It only takes one hour to shovel it out into a wheelbarrow and apply to the parts of the landscape you want to amend. That’s paying yourself $50 an hour.

Photo: Sifting compost in a Planting Justice permaculture garden

With regards to mulch, our research revealed that one company, Pacific Landscape Supply, is the supplier behind several of our main suppliers. A call to their office informed us that they source their fir bark mulch from mills in Oregon. The mulch is purchased by the railcar and trucked to whole-sale suppliers in Oakland where we typically purchase two cubic yards at a time to haul via pick-up truck to our job sites. Quite the journey for that single piece of mulch that was once part of a fir tree in the forest of Oregon. An alternative to this vast and intricate process is to establish relationships with local arborists or visit ChipDrop (a site that connects to local arborists. Arborist mulch (basically chipped branches) is typically sourced in town, which greatly reducing the environmental (and economic!) costs involved — all for a simple aesthetic compromise.

Photo: A permaculture client of Planting Justice prepares to receive chip drop mulch

Soil, a key ingredient in any organic garden, proves to be the most challenging input to find highly ecological suppliers for. High-quality soil for vegetable production includes many components (see table above), each of which is mined or sourced in disparate locations with broad-reaching environmental impacts. The permaculture alternative to importing organic soil is to improve the existing soil; however this can come with what appear to be substantial trade-offs. It takes time and effort to improve existing soil via cover-cropping and amending with compost. Moreover, vegetable gardens planted directly into existing soil face higher weed pressure, and thus require regular maintenance.

Given these trade-offs, it may feel easier to desire a quick solution – imported soil in raised beds. When we ask our clients to reconnect to their original intentions for growing a vegetable garden, the conversation can shift to include the environmental impacts of the materials required to grow that food. Perhaps it does make sense, and better aligns with overall goals, to start with a smaller garden. With this approach, and minimal additional effort, clients can produce their own organic compost on-site with locally sourced materials; and contribute to the gradual yet powerful work of rehabilitation. This work is both practical and cosmic—perhaps in learning to combat our own desires for quick solutions to complex problems, we build tolerance for the slow work of personal and political transformation; work that is necessary to create the beautiful future we believe is possible.

Photo: Seedlings planted directly into soil that has been amended and prepared in a Planting Justice permaculture garden

Photos: Months later, vegetables growing directly in ground in a Planting Justice permaculture garden

Compromise

To be sure, ecological installation involves compromise. As Toby Hemenway reminds us in his seminal book, Gaia’s Garden, “When it’s time to get our hands dirty, idealism runs into the brick wall of practicality. I’d rather see gardeners consume some nonrenewable resources to create eventually self-sustaining gardens than have them sit paralyzed by the fear of committing an environmentally incorrect act…. Especially in the establishment phase, when we’re working hard to restore abused land and heal broken cycles, we should be forgiving.”

As we investigate these compromises, we find ourselves facing some powerful and motivating questions about how to navigate a world in crisis with integrity and humanity. As these reflections bring to light new insights, we’ll continue to share what we learn – and hopefully readers will comment below with suggestions.

For folks who hire landscapers as well as for landscaping professionals themselves, we’ll close by saying that we are all part of many ecosystems—from the neighborhood up to regional and global scales. Let’s choose materials that do not undermine ecosystems near and far, seen and unseen. Let’s close local loops. The animals and plants are rooting for us.

Special thanks to the staff of Planting Justice for contributing to this post, and to Matt Sundquist for recommending Undermining.

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW WITH SUGGESTIONS/RESOURCES/QUESTIONS!

Selected Resources

0 Comments